Elements of Style

The highs and lows of the Costume Institute's Superfine exhibition

As promised, I’m following up May’s pre-Met Gala newsletter with some impressions from the Met’s Costume Institute exhibition, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, which closes today Sunday, October 26th.

Two days before I saw Superfine, I met a man named David in Hudson, New York. He was working in a shop stocked with the kind of beautifully constructed, wearable clothes that make you daydream about revamping your whole wardrobe. Our conversation began in the usual way: What brings you to town? Where are you visiting from? Where have you eaten?

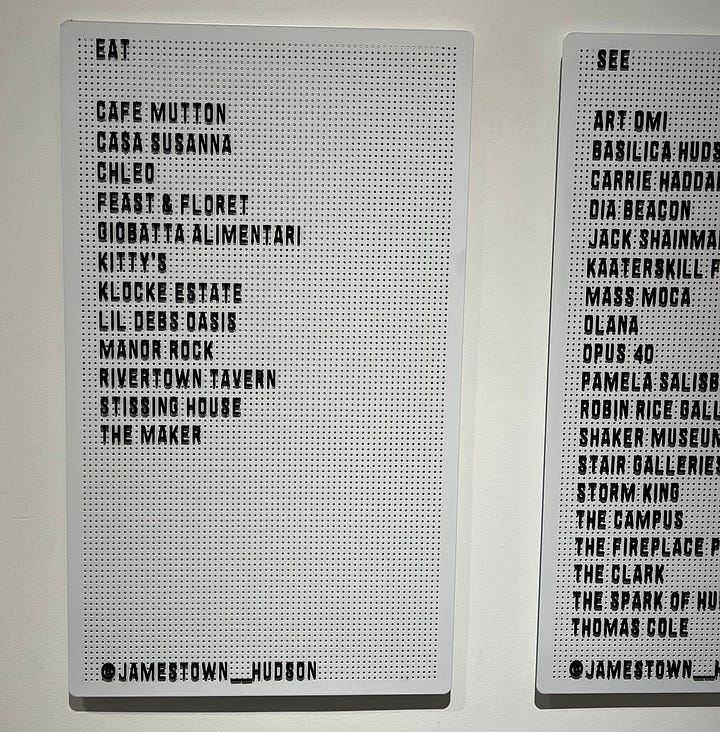

Once I finished answering his preliminary questions, David pointed to three peg letter boards in a corner of the shop with staff recommendations. You’ve visited some of our favorite places, he said approvingly. Having established a few similar sensibilities, our conversation could progress past small talk.

David had recently moved to Hudson from New York City to live with his partner. He studied art history, and even though he’s still settling into this new town, he takes regular trips back to the city to visit museums. When I told him my family and I were headed to the city next, he asked if we planned on seeing “the Anna Wintour show,” playfully referring to Superfine.

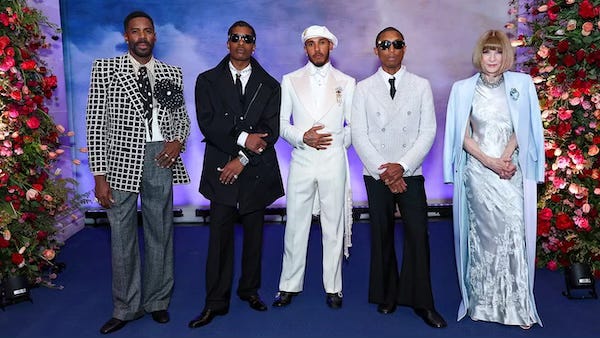

Technically, Anna Wintour has next to nothing to do with the exhibition itself. But the former editor-in-chief of Vogue magazine functions as a mascot for the Costume Institute. For the last thirty years, she’s chaired the Met Gala, the Institute’s biggest fundraiser. Under Wintour’s exacting direction, the gala has gone from a stuffy, modest museum fundraiser attended by Upper East Side ladies who lunch to an aspirational, celebrity-centric red-carpet event.

The gala attracts stars from all facets of culture, but Anna Wintour is the sun. She decides who gets the privilege of attending an event where, in 2025, an individual ticket cost $75,000 — quite the hike from 2023’s $50,000-per-person ticket. Unsurprisingly, Wintour’s version of the event has raised millions of dollars for the Institute. To acknowledge her efforts, in 2014, following a two-year renovation project, the Costume Institute space reopened with a new name, the Anna Wintour Costume Center. So even if Vogue’s cultural relevance craters into dust, Wintour’s legacy will shine on at one of the country’s oldest museums.

Yes, we’re planning on seeing the Anna Wintour show, I said, laughing and emphasizing her name.

That’s great, I think you’ll like it. I noticed David’s voice had taken a hesitant tone.

What are you not saying? I asked, fully aware I was dangerously close to getting too familiar with a stranger.

It’s good, it’s very well done, but there’s a lot to see and…it’s just a little…small. And I wonder why this specific exhibition didn’t get more space, you know.

I did know what he meant. Or at least I knew what I thought he meant. We spent the next few minutes discussing previous Costume Institute exhibitions we’d seen that seemed to sprawl across the Met’s galleries. And as we talked, our raised eyebrows, squinted eyes, and supportive nods danced around an unstated speculation that Superfine’s focus on Black style might have something to do with the exhibition’s compressed footprint.

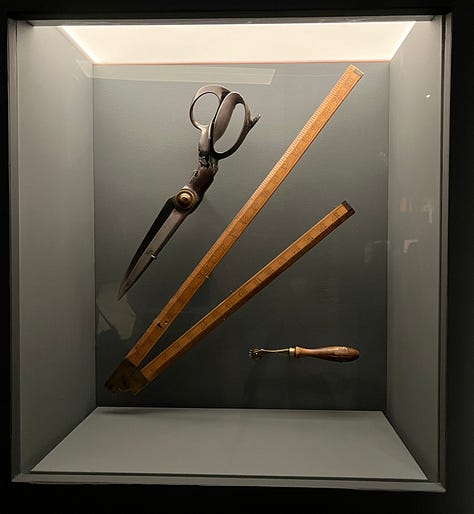

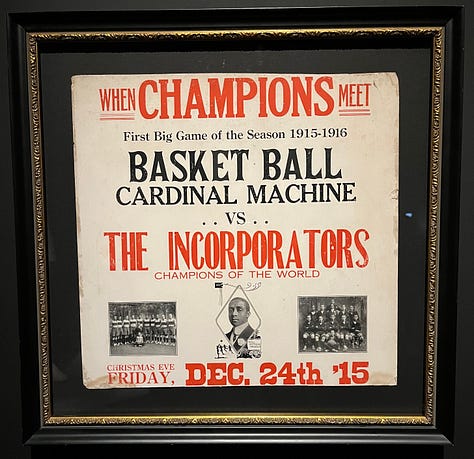

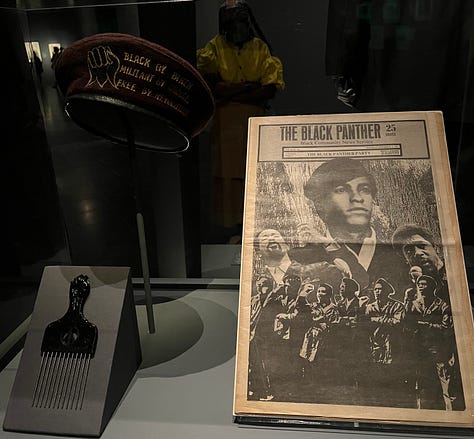

When I got eyes on Superfine a few days later, I realized that whatever the exhibition lacked in space, it made up for in objects. In addition to clothes, the curators Andrew Bolton and Monica L. Miller packed the galleries with portraits of 19th century entrepreneurs, the 1794 edition of Benjamin Banneker’s almanac, a display of early tailoring tools, a copy of a Black Panther newspaper alongside an Afro pick and Panther beret, video of the Nicholas brothers dancing, the A Great Day in Harlem photo, the A Great Day in Hip Hop photo, a 1915 advertisement for a basketball game, a perfect Barkley Hendricks painting, and several other things.

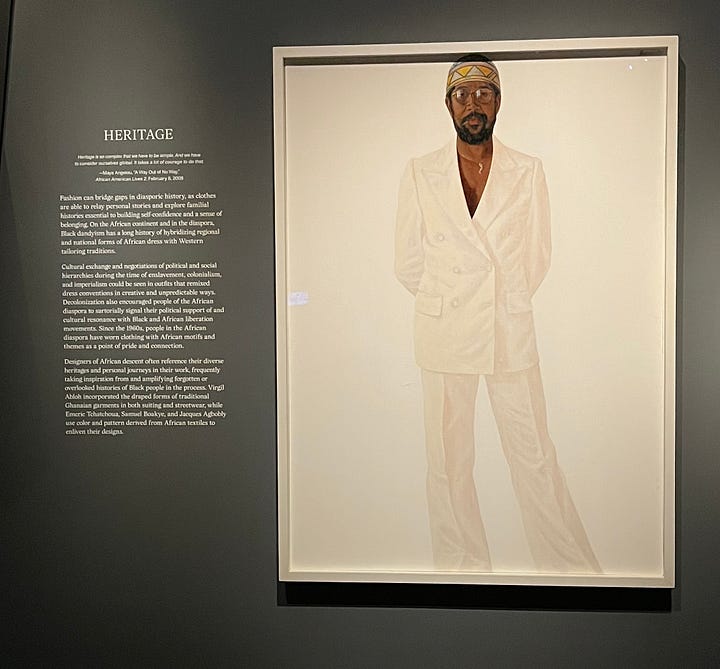

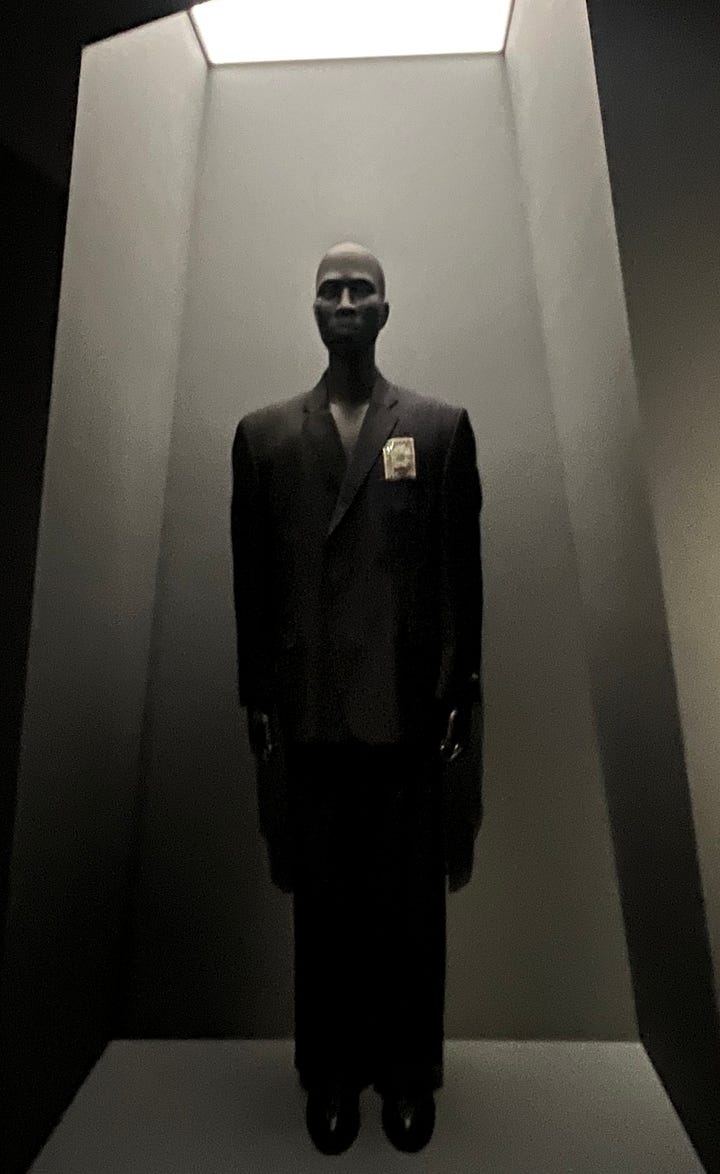

Bolton and Miller sort their bounty into twelve themes, each given an unimaginative, straightforward, single-word title like Ownership, Champion, Heritage, Cool, Cosmopolitan, Beauty. I like the idea of a theme as an organizing tool, but twelve of them felt excessive. The objects are grouped along obvious and simplistic lines. The Heritage section includes clothes made from African textiles. Louis Vuitton luggage trunks sit stacked in the Cosmopolitan corner. And clothes related to music, like a Dapper Dan jacket worn by Jam Master Jay of Run-DMC, and a contemporary outfit meant to represent the midcentury style of Miles Davis and John Coltrane, fall under the Cool umbrella.

In a video posted jointly to the Met and the Costume Institute’s Instagram accounts on June 14th, Bolton, the Institute’s curator in charge, described the exhibition as a “visualization and extension” of his co-curator’s book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. Bolton cited the current “renaissance” in menswear design led by Black designers as additional inspiration for the exhibition. He also aligned this exhibition with his department’s larger goals, saying, “In the Costume Institute, we’re always striving to make fashion a gateway to access and inclusivity by engaging with topics that reflect the zeitgeist.” It’s a subtle, tactful acknowledgment of the exhibition’s backstory.

Superfine’s story begins during the short-lived racial reckoning of 2020. That’s when Bolton started to think about meaningful ways to diversify the Costume Institute’s programming and collection. Miller’s book, published in 2009, appeared to offer a ready-made, intellectually sound foundation for an exhibition exploring the immense contributions people of African descent have made to fashion over the last three centuries.

But there are pitfalls to basing an exhibition on a dense academic text. Chief among them is the number of objects required to represent intricate research. Superfine includes some 200 objects, and not all of them are necessary. The inclusion of things like the knitted, kufi hat installed next to Barkley Hendricks’s painting of a man wearing a similar hat or the two paintings that each depict a jockey with a horse hanging on either side of a 19th-century jockey uniform seemed to be inspired by the academic impulse to cite or note any relevant research on a topic. But in a museum context, ideas can stand on their own, without superfluous visual support.

The exhibition worked best in the moments where the curators loosened their grip and entrusted visitors to interpret the objects on view.

Moments Like:

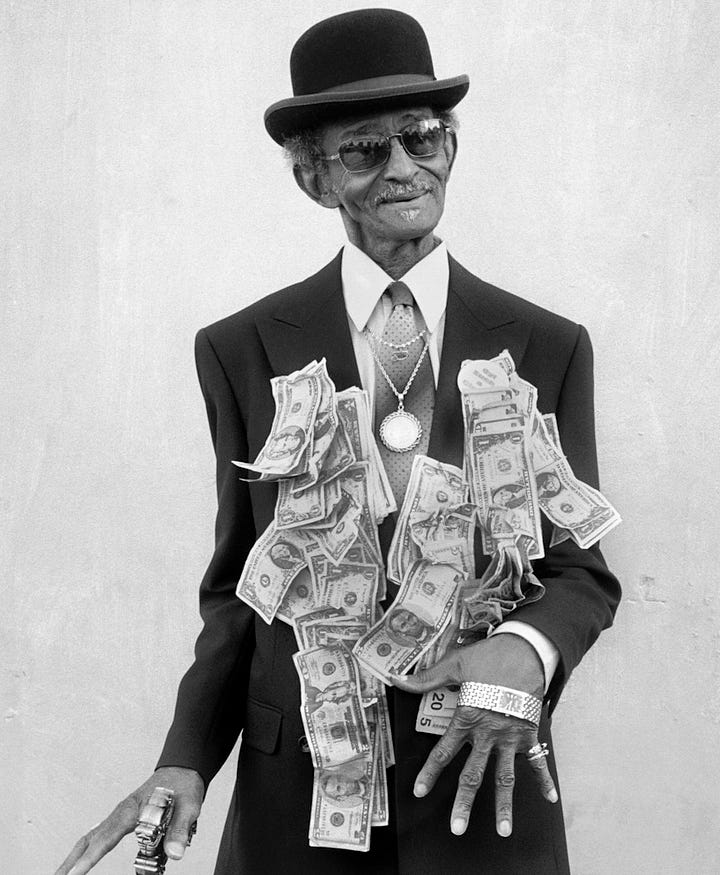

The Andy Levin photograph of New Orleans’s own musical legend, Uncle Lionel Batiste, wearing sunglasses, a top hat, and a suit jacket covered in cash for his birthday. In the photo, Uncle Lionel balances a cane in one hand and wears his watch over the other hand because if he kept it on his wrist, we might not be able to see it. And he wants us to see it.

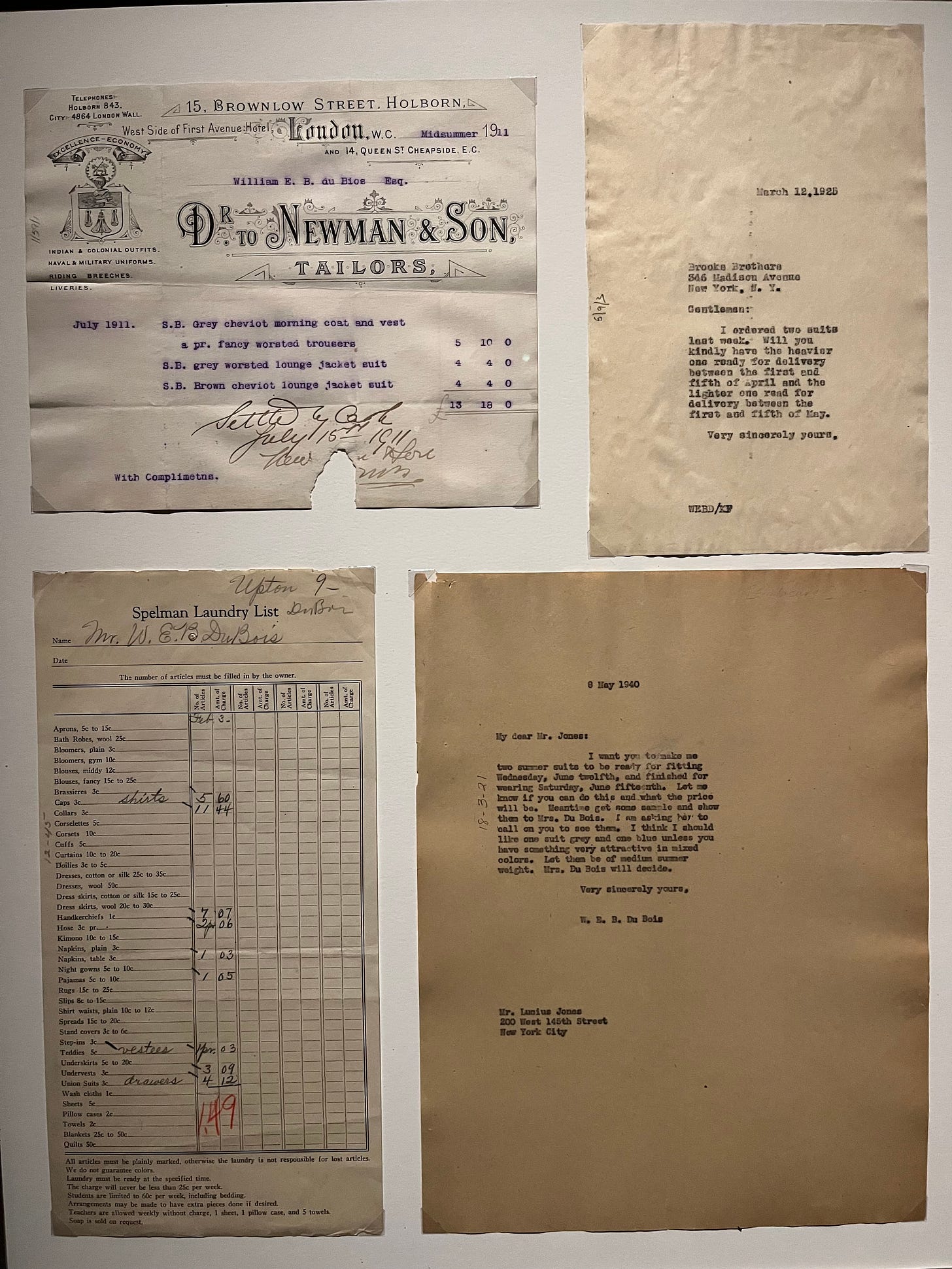

The display of W.E.B. DuBois’s correspondence with his tailor, along with his laundry list. In one letter, he requests two summer suits, writing, “I think I should like one suit grey and one blue unless you have something very attractive in mixed colors. Let them be of medium summer weight. Mrs. Du Bois will decide.” The vignette display added a humanizing touch to a man I’ve only encountered as a giant intellectual figure.

The shadowbox display of a Balmain belt that looks like a pair of hands holding a bouquet of flowers. At first glance I thought the belt was from the museum’s decorative arts department. Balmain’s creative director, Olivier Rousteing, drew inspiration for the belt from a photograph by the Ghanaian artist Prince Gyasi. In Gyasi’s photo a man in a red jumpsuit holds a bouquet of flowers.

And a Grace Wales Bonner velvet set accented with hand-embroidered cowrie shells and Swarovski crystals. The look is from Bonner’s 2015 debut collection, where she used literary works like James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man as references.

In each of these moments, the objects showed how style works. How it’s not just what you wear or design but how you wear things or design them that signals a set of beliefs, a worldview, an origin story. These objects, in particular, show how a person’s style is an attempt to capture, distill, and communicate the breadth of their interior life.

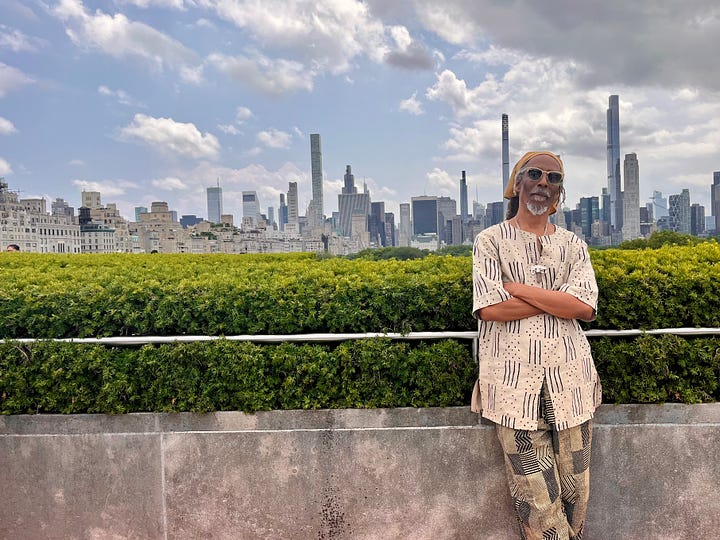

Towards the end of our conversation, David complimented my outfit. I noticed it when you walked in, he revealed, using his approving tone once again. Maybe our whole encounter was just an example of excellent customer service, but I’d like to think it was also (primarily) an example of how style creates shortcuts to connection. And I mean style in the broad sense, like the places where you choose to eat, the ways you choose to fill your spare time, in addition to the clothes you choose to wear while doing those things. Style, expressed as a series of ways of being, is what allowed David and I to find common ground in a passing moment on a Saturday morning.

I purchased two handcrafted, leather-bound beaded bracelets before leaving the shop. I’m happy I own something that holds the memory of a delightful encounter.

The Extras

In grad school I wrote my thesis about the Costume Institute so being able to see Superfine with my family made me really happy.

Thanks for reading!

You never go out of style! Sounds like David was someone with vision and I’m glad you two connected. Thank you for sharing your experience of the exhibit. It looks like there was a lot of really great aspects along with room for improvement. I am hopeful this is the first of many such exhibitions and we will see the curators make new and perhaps better decisions with each new endeavor. Methinks they should bring in a curatorial consultant that has innate style and vision along with a depth of knowledge on fashion, art, and culture and experience in the field. And I know the perfect person…👼🏼

Louisiana is an old soul (heel included)…

the boot that France kicked off after its inability to refine the vestiges of its own inner conflicts with sugar cane, cotton, and skin color.

A couple hundred years later my cousin Charles was one of the first African Americans to integrate Louisiana State University in New Orleans. Charles later served in the Peace Corps, stationed in Kenya🇰🇪 before finally settling in Harlem, New York.

A few years ago I had reconnected with Charles through social media. By then I’d gotten divorced and was living in Brooklyn. I’d also been wondering about an artist whose work kept appearing on Art page of which I’d subscribed. The artist. had the same last name as my cousin. Well, lo and behold…the artist was indeed Charles’ daughter.

A couple of years later, after visiting Charles on the east coast Charles’ youngest daughter, graciously invited my family (the five of us-plus 1, whom she’d never met) to her wedding.

It was an honor to witness this beautiful young couple exchange their vows in such a picturesque setting.

There’s no way to display, in words or in any social context, the sense of realizing exactly what it means to belong to those who are most important. In the most humble sense, I belonging to my family. Through your unconditional love, you all have held me down and kept me rooted through it all. And for that I am grateful.

A couple of days later we went to The Met.

Thank you so much See Level!