We See Each Other

Some notes on portraiture.

Last week I included a painting of the late actress Cicely Tyson with Miles Davis in the newsletter. Recall if you will that the painting, Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas, by the artist Henry Taylor is based on a photograph taken by Ron Galella. In a comment about the artwork, my father began by pointing out “what’s missing.” For him, the painting did not express the fullness of Tyson’s spirit. His comment speaks to the challenge of making a portrait. How does an artist represent a person?

Ancient Egyptian artisans created unadorned depictions of Egyptian royals and elites in the form of sculptures, wall reliefs, and paintings. These works look plain by today’s visual standards, but that might be because they weren’t made for the living. Ancient Egyptians believed that a person’s soul could live on in an object that portrayed their likeness; these portraits were intended to provide a practical, eternal home for souls.

In the 1434 painting, Arnolfini Portrait Renaissance painter Jan van Eyck chose to depict his subjects, the Arnolfinis, in an interior setting letting their furnishings and clothing represent their comfortable position in society. In 2021 we have Zoom. Those people who conduct Zoom calls in front of curated bookshelves or countertops with vases of fresh flowers and bowls of fruit participate in a centuries-old tradition of using objects as a substitute for personality. You really hate to see it.

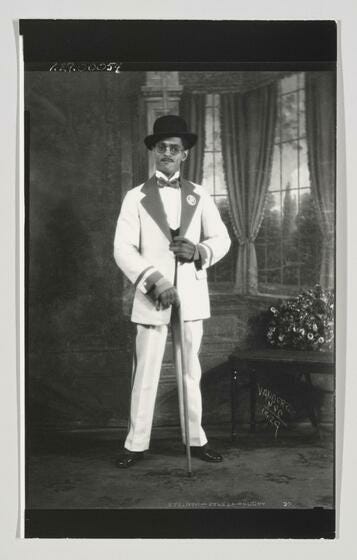

Photography changed the portrait-making game forever, offering more people the opportunity to see themselves in two dimensions and freeing painters from the obligation to represent their sitters’ detailed likeness. The work of photographer James Van Der Zee, who operated a busy studio in Harlem in the 1920s, exists as a visual record of the area’s Black middle class. His 1929 photograph On The Town shows the care his clients took in having their picture taken. Van Der Zee’s male subject is dressed in a white suit with a top hat and cane, posing in front of a backdrop meant to reference Victorian-era paintings’ backgrounds.

British painter Lucian Freud, grandson of Sigmund, used his portraits to explore his subjects’ psychological state. I suppose the apple’s apple remains relatively close to the tree as well. Freud’s post-photography paintings show people not as we see them but as we feel them.

Just as the same 12 notes have been used to create the vast array of sounds we call music, artists have found countless ways to show us ourselves throughout history. Portraits, like songs, are a collaborative effort; a good artist like a good music producer can see what makes their collaborator unique and makes it their job to draw forth that sense of individuality. A great artist or great producer translates individuality into something universal, becoming a vessel through which something relatable arrives. Like music, the best portraits elicit an emotion or two in the audience.

Back to my father, he has a theory that if you’re trying a new ice cream place or brand, you should sample their vanilla first. If they can get that right, you can proceed with more adventurous flavors. I take a similar approach with artists. If an artist has portraits as an element of their practice, my response to those works usually indicates how I feel about their entire oeuvre.

I’ll leave you with two examples of portraiture that I think are worth sharing.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

The first time I saw Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings, I assumed she knew the people in her work. Once I learned that her portrait subjects are people she imagines, I began to look at them differently. Like rewatching a movie with a big plot twist, I revisited her work looking for clues of these peoples’ nonexistence. The paintings began to take on an otherworldly quality. They started to look like the part of a dream that lets you know what’s happening isn’t real. You were in my dream, but you were surrounded by crows. We were dancing, but we were all dressed alike in an empty room.

There is something haunting about Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings, and since they’re not of real people, there’s no chance old souls have taken occupancy within her canvases. The haunting comes from the mystery inherent in the work. Portraits rarely cause us to ask why they exist. Our vanity lets us assume a legitimate reason for just about any representation of another person. But Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits do make me wonder why she paints them, aside from the obvious fact that she’s a damn good painter. Without fail, the more I try to explain or make sense of Yiadom-Boakye’s works, the more unknowable they feel for me. Maybe the mystery is really just magic?

Adrienne Salinger

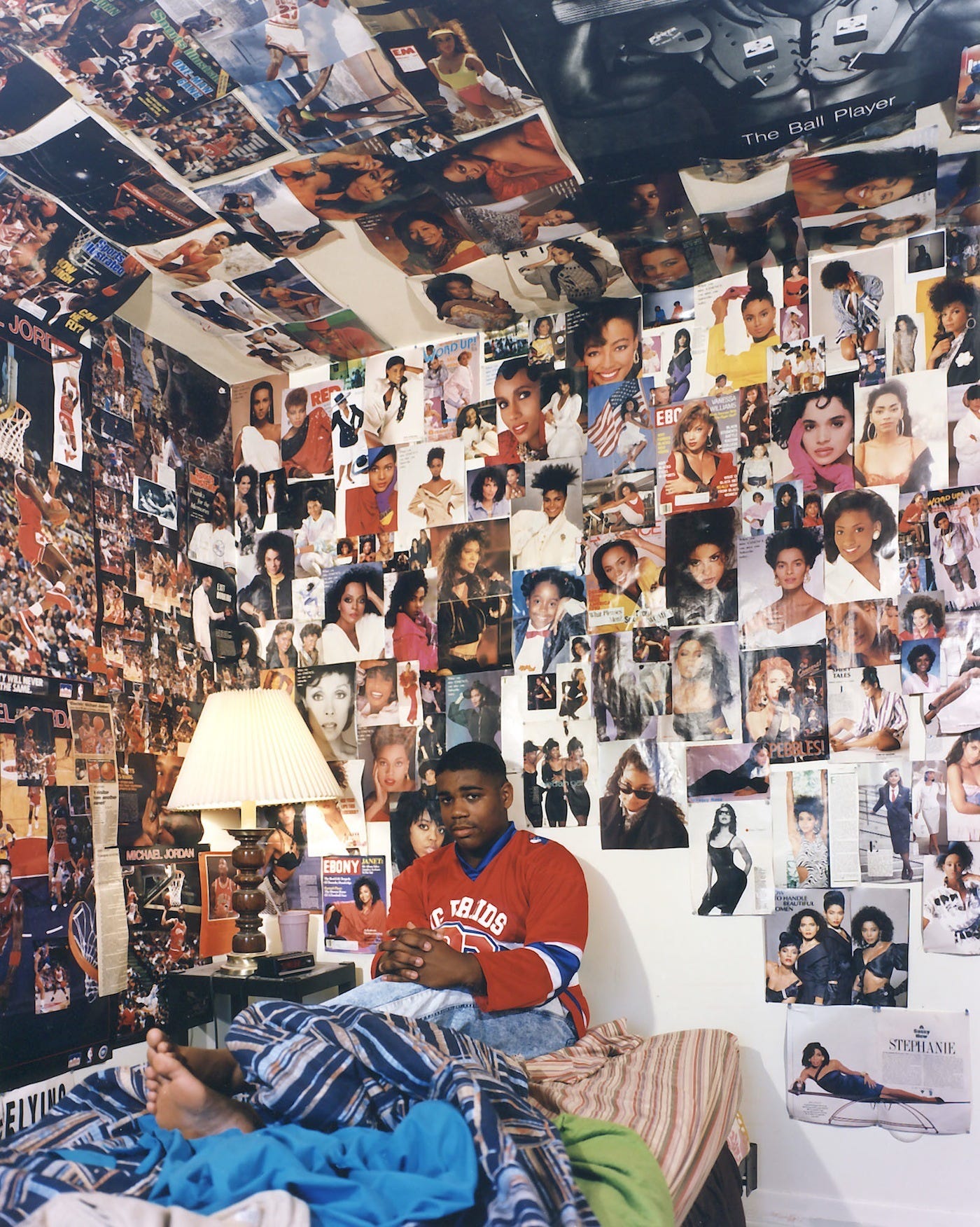

Adrienne Salinger’s photographs have been on my mind for almost a year now. In particular, her early 1990s series In My Room: Teenagers In Their Bedrooms. As the title states, the works show teenagers in their bedrooms surrounded by their stuff like the Arnolfinis in van Eyck’s painting. Although unlike van Eyck, Salinger conducted in-depth interviews with her subjects, which revealed the complexities of their developing personalities.

The early isolation of 2020 left me a lot of time to consider how this quest for and need to express identity doesn’t end once you emerge from adolescence. Throughout our lives, we make declarations of who we are most obviously through our consumption habits. But also through our networks and habitual practices. Being cut off from those things for a while last year felt destabilizing, but I found a lot of comfort in listening to music and watching shows I liked as a teenager. Perhaps either Freud could explain why that was the case.

I also spent a lot of time on Instagram last year. Instagram asks us to present ourselves, our idealized selves. The app overflows with pictures of people planting and waving their little identity flags, sharing their skincare products, furniture finds, what they’re reading, what they’re eating, who they’re eating with, what music they like, and on and on. I admit this part of social media can be very annoying, but it’s also sort of innocent, each post a small self-portrait. It’s hard to resist participating on occasion. The teens in Salinger’s work probably could not have predicted how central the (digital) possession and display of images would become to so many of us “grown-ups.” Couldn’t imagine that we’d spend stupid amounts of time fussing over our grids and stories the way they carefully arranged the pictures on their bedroom walls. We might not be teenagers anymore, but we still want to be accepted and, above all, seen.

Extra points for those of you who caught the Real Housewives of Atlanta reference in this week’s newsletter title.

QUESTION OF THE WEEK:

What’s a song that reminds you of your youth and still sparks joy?

Thank you for reading.

Songs by No Limit Records and Ca$h Money Records spark joy of my youth at first and then spark shame by the mysonystic and problematic lyrics. Annnd also Jay-Z songs up until The Blueprint album will always spark joy.... and also randomly songs from Jagged Little Pill by Alanis. Annnd also 90's sitcom theme songs! Okay I am done. Bank my points for all of the Housewives references I catch. Thank you.

It’s an album, but: No Doubt’s Tragic Kingdom. I periodically test it for relevance and it always passes with flying colors. At that moment in their identity, they were exactly enough weird, exactly enough powerful, and exactly enough vulnerable.